The startup organisation is one of the greatest business formats to help make the world a better place, and startups can take many forms. Take a group of people with the right goals and equity incentives and organise them in a startup, then you can unlock human potential in ways never before possible, and get them to achieve amazing things.

But, if startups are so great, why do so many fail? If fact, as many as three out of four venture backed startups will fail within five years (Harvard Business School 2017).

Anyone who has built companies has had both successes and failures, and many people who instigate startups have had both. The key is that they likely learnt just as much from their failures as their successes.

To be analytic about startups, you have to avoid some of the instincts and misperceptions people have from the stories of the many successes and failures that have hit the mainstream news and that they’ve seen over the years.

The factors that most influence startup company success

There are, generally speaking, five factors. First is the idea, and many people think that a good idea is everything.

But then, once you go from idea to building something, you need people. So second is the team, their execution and adaptability, and often that can matter more than the idea.

The third factor is the business model. The route the company has and that clear path to generate customer revenues. Even though there are many billion pound companies with minimal profit, the key to real success is making a reasonable level of profit all the time. Without any profits, then companies can’t really call themselves a success.

Fourth there’s funding. Companies that have a good idea often receive large amounts of early funding, but often it’s because they presented their idea and business model to funders clearly and succinctly.

Finally, there’s timing. If the idea is too early for its target customers then, whilst it may be great, if the world just isn’t ready for it then it can fail. Go too early and you have to spend time and money educating the world about what your new thing is and exactly why they might need it. The timing could be perfect, of course, or it could also be too late, in which case there might be too many people who already have your thing to make money, or too many competitors to gain market share.

If you look very carefully at all of these five factors across lots of companies, there are trends. Many wildly successful billion-pound companies and organisations that flopped both had intense funding and good business models, but some succeeded and some failed. There are lots of factors at play, of course. But one that stands out. The number one success factor is timing.

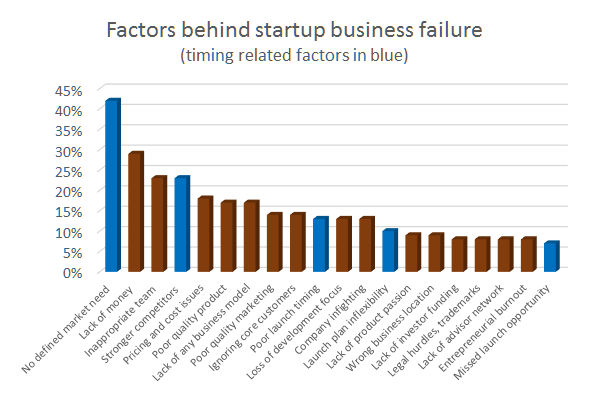

Timing accounts for a third to a half of the difference between success and failure, depending on the market sector. Team and execution came second, and differentiability and uniqueness of the idea came third. Part of timing is launching a new product when there’s no main competition. So that means you get majority market share early, and also get the opportunity to set a market price that makes money.

Obviously this isn’t definitive. It’s not to say that the business idea isn’t important, but what matters most for business success is that the idea gets into the market at just the right time.

The last two factors, business model and funding, make sense being fourth and fifth, because you can start out without a business model and add one later if your customers demand what you’re creating. The same goes with funding. If you’re underfunded at first but gain traction with customers, it’s relatively easy to get the funding.

An example of timing success is Airbnb. This company was passed over by many investors because they thought, ‘No-one is going to rent out any space in their home to a complete stranger.’ But a key reason Airbnb succeeded, apart from having a good business model, a good idea and execution, was the timing. The company started during an economic recession when people needed extra money, which helped the people renting out their homes overcome their normal objection to rent out their own home to someone they didn’t know.

The same is true of Uber, a good company and business model, with great execution. But their timing was again perfect, matching their need to get drivers and their own cars into the Uber system matching drivers on the hunt for extra money.

So what about failures? Z.com was an online entertainment company. It had raised enough money, had a great business model, and even had good Hollywood talent signed up to join the company. But broadband penetration was too low in 1999 to make it work for its customers. It was simply too hard to try and watch video content online, you had to put codecs in your browser, and do other technical things to make it work, so the company eventually went out of business in 2003.

Two years later, YouTube had a minimal business model at its start, so it wasn’t certain it would work out. But, at launch, the codec problem was solved by Adobe Flash, just as home broadband penetration crossed 50 percent in the US and Europe. So the launch of YouTube was perfectly timed. A great idea, combined with beautiful timing.

Summary

Start ups can change the world and make it a better place. Insights into what works help create a higher success ratio, and enable something great to be launched in the world that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

Execution definitely matters a lot, as does the business idea, but timing often matters a lot more. The best way to really assess timing is to really look at whether your target consumers are really ready for what you have to offer them.

Even if you create a business around something you really love, and you want to push it forward, you have to be very honest about assessing its launch timing. Be really truthful to yourself about it, research the market and don’t be in denial about any poor results that you see. Of course you can always change your product, positioning or marketing. After all, everyone wants to be in the twenty percent that succeed, rather than a startup that fails.